|

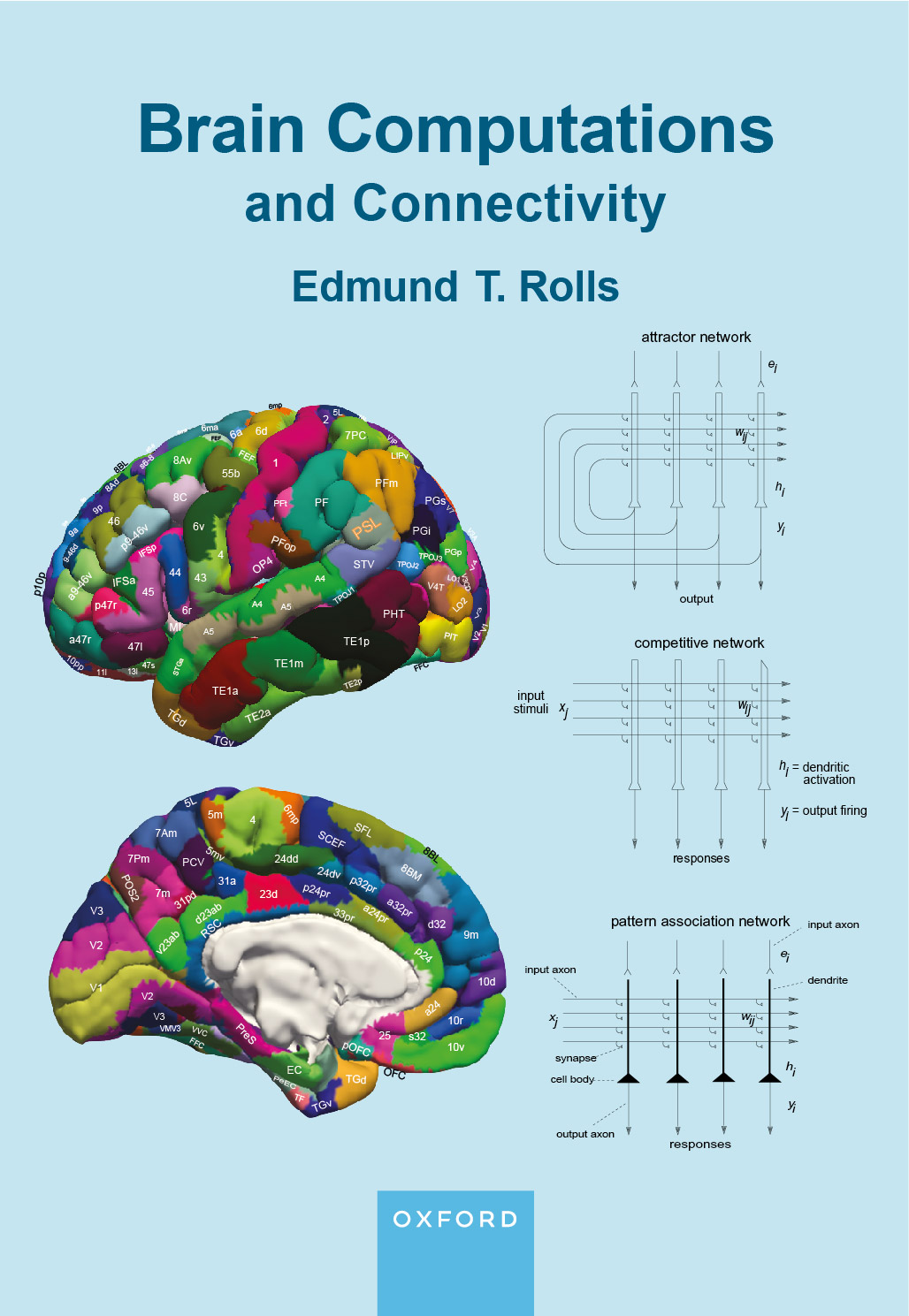

Overview: Rolls

has made discoveries about the brain bases of mental disorders that

have their foundations in his interests in emotion and in computational

neuroscience (B16). Rolls and colleagues

have discovered that depression can be related in part to increased

connectivity and sensitivity of the non-reward related lateral

orbitofrontal cortex and decreased connectivity and sensitivity of the

reward-related medial orbitofrontal cortex (626,

B13, B16, 679). Rolls and colleagues have

related the symptoms of schizophrenia to altered stability of cortical

attractor networks (631, 629),

in turn related in part to reduced forward relative to backward

connectivity in the cerebral cortex (602).

These approaches have been extended to the memory changes in normal

aging (540),

to autism (541, 609),

to obsessive-compulsive disorder (449), to ADHD (629), and to the emotional

changes that follow brain damage in humans (641).

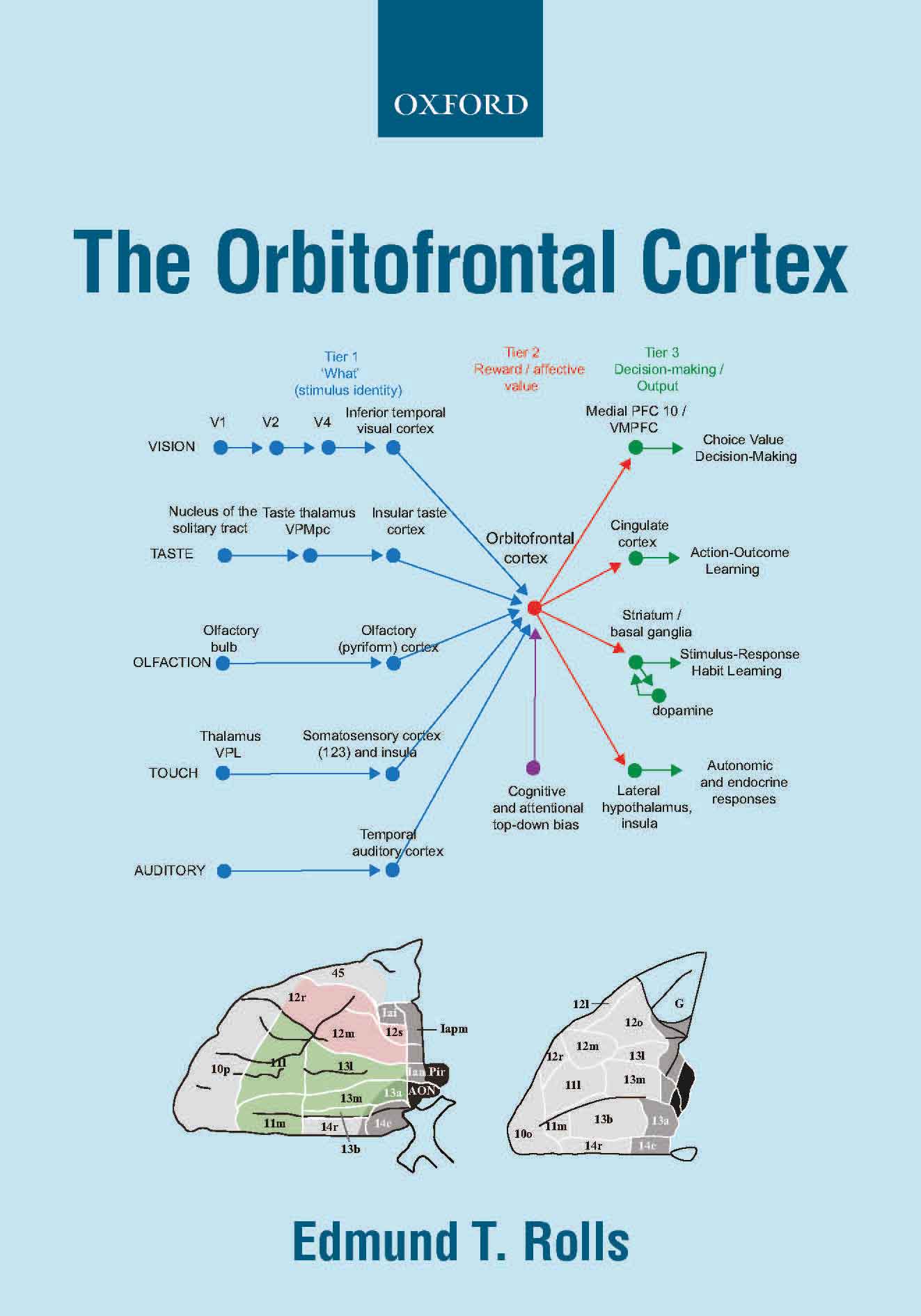

Depression

A

non-reward attractor theory of depression, in which the lateral

orbitofrontal cortex attractor network system for non-reward maintains

its activity for too long; and the medial orbitofrontal cortex reward

system is less responsive (559,

572, 579,

626, 679, B12, B13, B14, B16). The theory

is supported by a model of the computation of non-reward in

the orbitofrontal cortex (562).

An introduction to the theory is available as a lecture.

The lateral

orbitofrontal cortex and adjoining inferior frontal gyrus (615)

in depression has increased functional connectivity (564, 591, B14, 626, B16) with

the precuneus (where the self is represented, and which may contribute

to the low self-esteem in depression) (592);

with the angular gyrus (involved

in language, and which may contribute by a long loop attractor to the

negative rumination in depression); and with the temporal lobe cortex

(which may contribute to the sad interpretation of faces and

events) (564).

Effective or directed connectivity from the medial orbitofrontal cortex

to the lateral orbitofrontal cortex is increased in depression, and

given that the activity in these areas is reciprocally related, this

may release the lateral orbitofrontal cortex into high activity, which

was found in the analysis (583).

Rolls' theory of

depression (559,

626,

B13, B14, B16) is

also supported (626, 679) by increased functional connectivity of the

non-reward-related lateral orbitofrontal cortex (615,

626)

with the posterior

cingulate cortex (588)

which provides a dorsal route into the hippocampal memory system (584),

and decreased functional connectivity of the reward-related medial

orbitofrontal cortex with the parahippocampal gyrus (564)

which provides a ventral route into the hippocampal memory system, with

both effects enhancing sad and reducing happy memories in depression (615,

626, B16).

A pregenual

/ subcallosal subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex normally

with high connectivity with the medial orbitofrontal cortex reward system

has increased functional connectivity with the

lateral orbitofrontal cortex non-reward system in depression. This may provide a mechanism for more non-reward

information to be transmitted to the reward-related part of the

anterior

cingulate cortex, contributing to depression (596).

The amygdala has reduced functional

connectivity in depression (590).

The importance of the orbitofrontal

cortex, a key brain area for emotion, in depression (626)

is supported by an

activation study in the monetary incentive delay task (623).

This shows that the sensitivity of the lateral orbitofrontal cortex to

non-reward (not receiving an expected reward, a contingency that can

produce sadness) is higher in adolescents with a high severity of

depressive symptoms. Further, the medial orbitofrontal cortex is less

sensitive to reward in those with a high severity of depressive

symptoms (623).

This provides further key evidence relevant to the theory of

depression (559,

626,

B13, B14, B16, 679).

An overview of the brain mechanisms of depression, and

how this fits in with understanding of the brain mechanisms of emotion (626, 674)

is provided in The Brain, Emotion,

and Depression (B13). This approach

to depression has

implications for treating depression both psychologically and

medically (559, 679,

B13, B14, B16).

Depression, and

behavioural and depressive problems are associated in children with

sleep problems and with lower volumes of brain regions such

as the prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate

cortex (616).

Lower volumes of these brain regions are also associated with

behavioural and depressive problems in children of mothers with

prolonged nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (622),

in children of young mothers (642),

and in children in families with family problems (636).

Childhood trauma is associated with mental health and cognitive

problems in adults, and the association is mediated by functional

connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex, prefrontal cortex, and

temporal cortical areas (651).

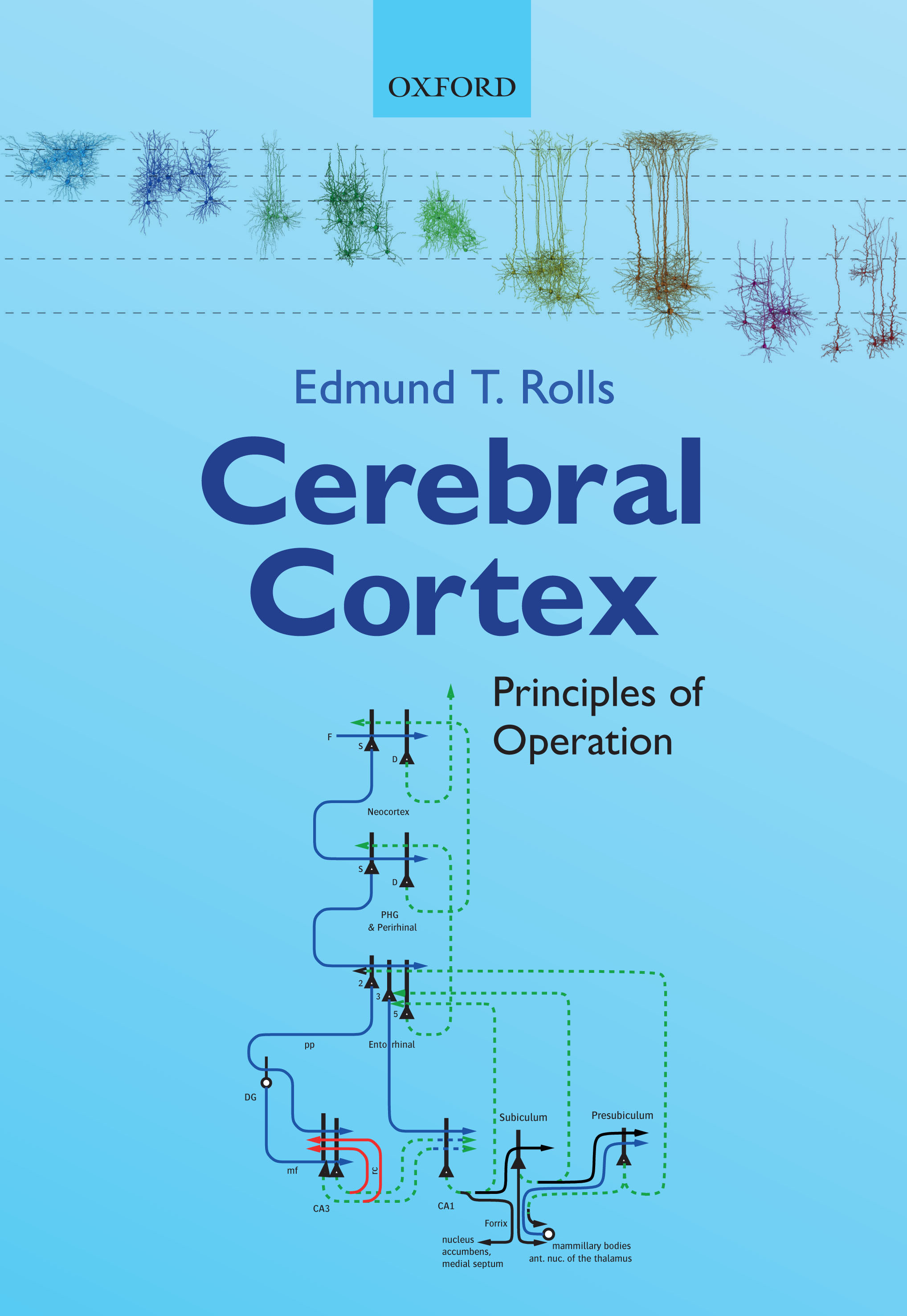

Schizophrenia

A theory of schizophrenia in which

reduced glutamate functionality in the prefrontal cortex destabilizes

attractor networks producing cognitive impairments in attention,

and exceutive function; and in which reduced glutamate function

in the orbitofrontal cortex leads to the negative symptoms. Increased

activity in medial temporal lobe networks overstabilizes attractor

networks there leading to the positive symptoms including

hallucinations and delusions. (450,

490,

496,

503,

602,

B12, 631, B16, 681).

The discovery in a sample of 2,567

patients with schizophrenia that the main variation between individuals

is in the negative symptoms, using the PANSS (580).

This has

implications for stratified treatment.

In first-episode

patients with schizophrenia the main changes in functional connectivity

involve the inferior frontal gyrus; and become established in thalamic

connectivity in the chronic state (563).

The temporal variability of functional connectivity is increased in

schizophrenia, is related to lower functional connectivity, and may

underlie the thought disorders (629).

Increased functional

connectivity of the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex is related

to volition (thought control), and is not treated by neuroleptic drugs

(538).

In schizophrenia,

we provide evidence that goes beyond the disconnectivity hypothesis, by

showing in a large sample of people with schizophrenia that whereas the

effective connectivity in the strong or forward direction is reduced,

the effective connectivity in the weak or backward direction is not (602).

This may tend to result in over-emphasis on the internal world, with

relative disconnection from the reality of the external world (B16).

Autism

A middle temporal gyrus / superior

temporal sulcus (STS) region involved in face expression processing and

theory of mind has reduced cortical functional connectivity with the

ventromedial prefrontal cortex which is implicated in emotion and

social communication. The precuneus, which is implicated in

spatial functions including of oneself, has reduced functional

connectivity. These two types of functionality, face

expression-related, and of one’s self and the environment, are

important components of the computations involved in theory of mind,

whether of oneself or of others, and the reduced connectivity within

and between these regions is proposed to make a key contribution to the symptoms of

autism (541,

570,

609).

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

A theory

that hyperglutamergia in the prefrontal and premotor cortices in OCD

overstablizes attractor networks in these regions (449,

B14, B16).

Effects of damage to the human

orbitofrontal cortex

Impairments

in the rapid reversal of associations between stimuli and reward value

in

patients with selective lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex and related

areas and

their relation to emotional changes (188, 203, 331, 354, B14, 641).

Also, impairments in

impulsivity (353,

362,

394).

These discoveries were

inspired by the discoveries

on neuronal activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, and are relevant to

understanding

the changes in patients with frontal lobe damage and in patients with

borderline personality disorder (B16).

A recent discovery is of the effective connectivity

of the human orbitofrontal cortex, vmPFC and anterior cingulate

cortex, which shows how reward value and emotion can reach the

hippocampal memory system to become incorporated in episodic memory

(649, 657, B16).

This also shows how these cortical regions have connectivity

with the septum and basal forebrain cholinergic systems, providing a

mechanism that may contribute to the memory impairments produced by

damage to the orbitofrontal cortex / vmPFC and/or anterior cingulate

cortex in humans (649, 657).

Addiction

The medial

orbitofrontal

cortex reward system has high functional connectivity in those who tend

to drink alcohol and who are sensation-seekers and impulsive; and

the lateral orbitofrontal cortex non-reward system has low functional

connectivity in those who tend to smoke, and are impulsive for a

different reason (599).

The medial orbitofrontal is also activated by amphetamine (367). These

discoveries underline the different neural bases for different types of

addiction (B14).

Normal Aging

A theory

of how reduced stability of cortical attractor networks can

account

for some of the memory and cognitive symptoms of normal aging, with implications for treatment (540, 613, B16).

Hypertension

and impaired memory

Even moderate hypertension is

associated with reduced hippocampal functional connectivity and

impaired memory (625).

Brain, cognitive, and psychiatric differences associated with development

We have discovered a

constellation of somewhat similar functional and structural differences

of the brain (e.g. of the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate

cortex, and hippocampus) that are associated with lower cognitive

performance and with mental health symptoms including depression. The

factors associated with these differences include childhood traumatic events ( 651), the family environment (636), low age of the mother (642), prolonged nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (622), and low sleep duration (616).

|